© XAVIER RIBAS - Afterlife (2020) 9 Pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Gloss Baryta + 1 Pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Satin, 57 x 76 cm each. Ed 3+1ap

Afterlife (2020), 10 Pigment prints 57 x 76 cm each.

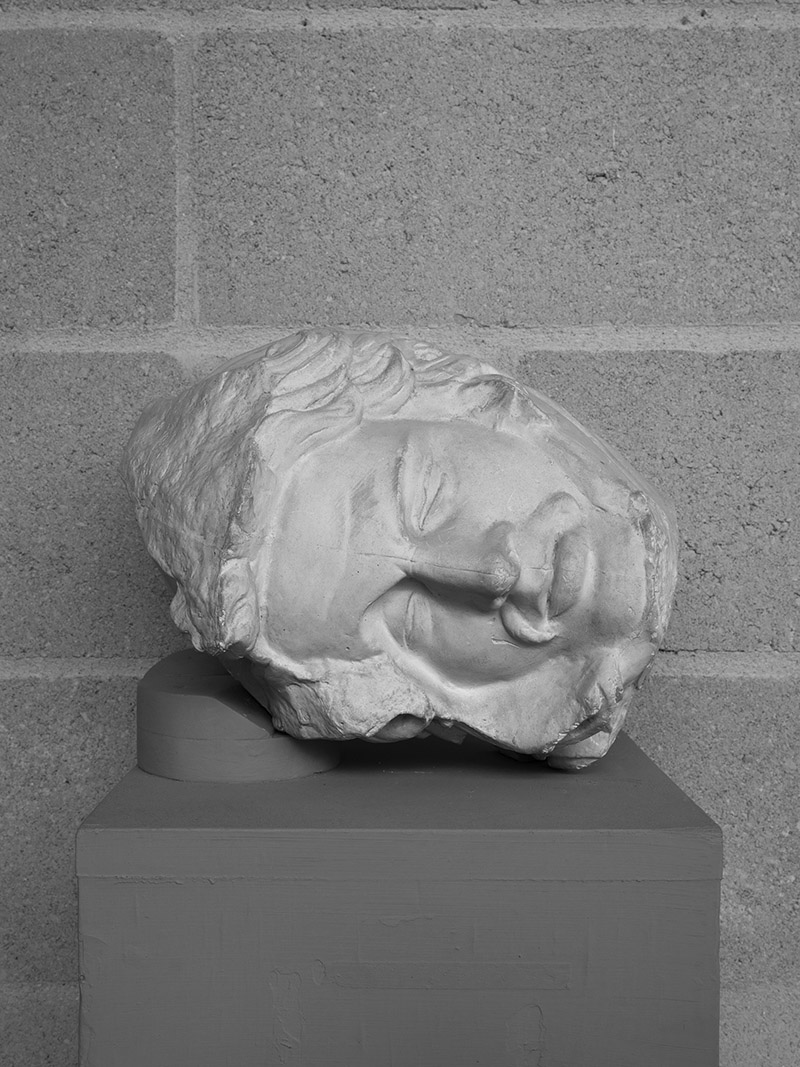

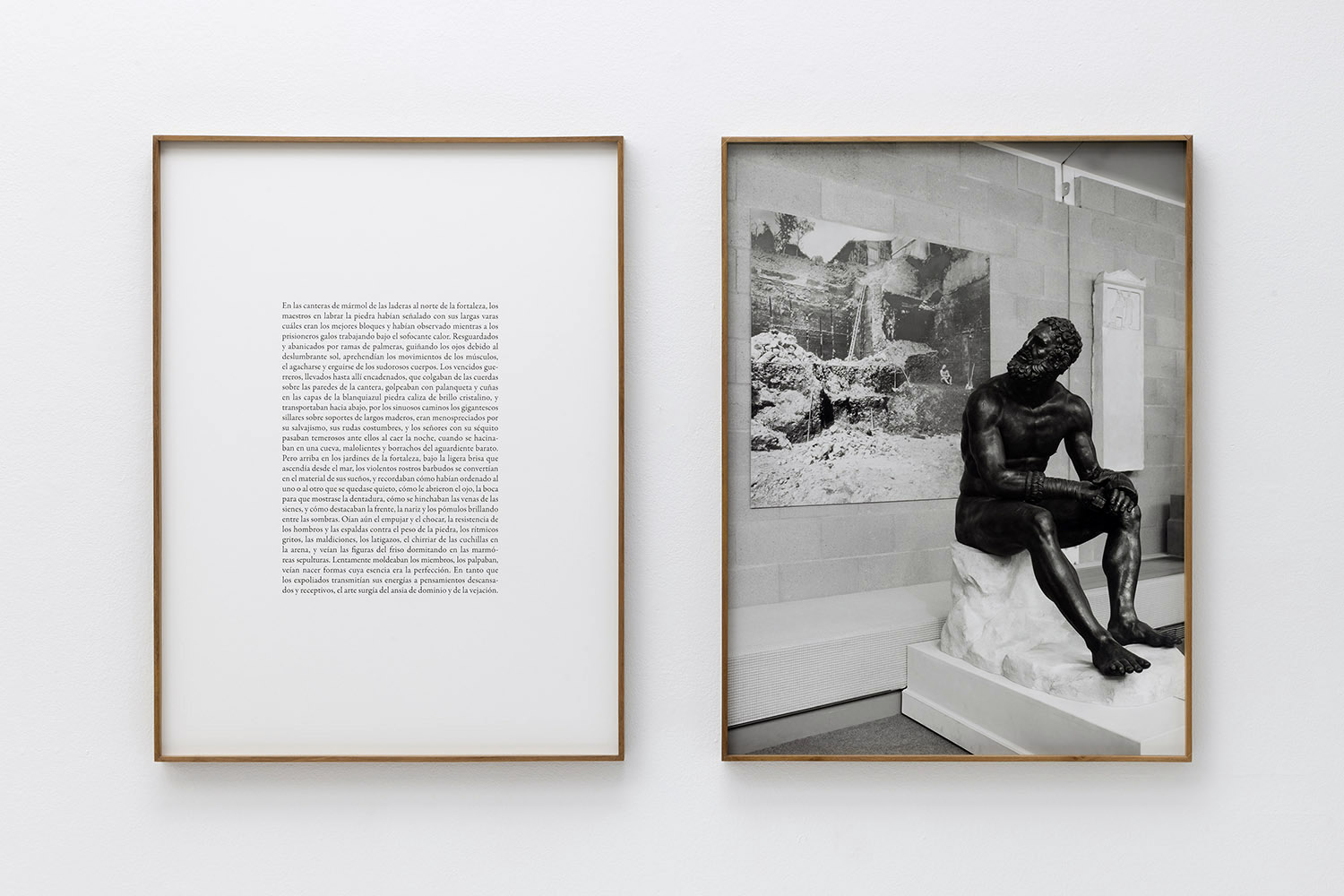

Afterlife is composed of nine photographs and one text excerpt from Peter Weiss's novel The Aesthetics of Resistance (1975). The photographs document plaster casts in the collection of the Museum of Classical Archaeology at the University of Cambridge, made from sculptural fragments preserved in museums around the world. Peter Weiss's text describes the scene of the construction of the Great Altar of Pergamon, inspired by the archaeological remains in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Weiss evokes the process of extracting the stone blocks in a quarry near the place where the monument is being built, in which masters, sculptors, slaves and prisoners of war coexist in a relationship of production and inequality, while the bodies of the workers serve as inspiration for the sculptures for the frieze.

---

Ancient monuments, now reconstructed as ruins in archaeological parks and museums, are presented as unified, positive objects with a tangible past that “ought not to be disturbed” (Gastón R. Gordillo, Rubble. The Aftermath of Destruction, 2014, 6). However, ancient monuments and their sculptural elements cannot be considered separately from the damaged bodies of the labouring force who extracted the stones and were engaged in their construction. The defeated bodies of slaves and war prisoners resurface from the rubble of ancient temples and palaces with the sculptural fragments of Gods, Lapiths, Giants, Centaurs and Amazons. The museum displays of ancient remains are haunted by violent histories and by those ‘enlaboured’ bodies, their presence marked on stone.

The plaster casts of ancient sculptural fragments, like ghosts and spectres of the original stones, respond to the desire to unfix the unique and fragile artworks to disseminate their histories and knowledge worldwide. Although the making of plaster casts dates from antiquity, it was only in the 19th century that they became part of national museum's collections and displays, such as the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, with the purpose of educating larger audiences. Since collecting archaeological remains from all over the world was part of the colonial project of western imperialism, one may ask what histories were to be disseminated with the plaster casts of ancient remains and what histories were to be disregarded. In their humble status as reproductions, the plaster casts offer an opportunity to begin to unlock our attention from those original and unique objects and direct our thoughts, as Adorno put it, to their constellations, to their historic positional value in relation to other objects, and to the processes stored in them (Negative Dialectics, 1973, 163). Reorienting our thoughts from the objects to their constellations will allow us to pay attention to material histories and to the multifaceted textures of human labour.

The photographs of the plaster casts are ghosts and spectres once again of those original sculptures, ghosts of ghosts, spectres of spectres. Their framing aims to conjure the dim histories of the human bodies who worked the stones out from the quarries and into the realm of art: to evoke those labouring bodies by showing less and closing in. I would like to suggest that the afterlife of those ancient bodies – which were fixed and immobilised as the labouring force of extractive and violent economies – negated and destroyed in the creative act of monumental construction, is held in the missing limbs, heads, faces, torsos that were left in the rubble, unrecognisable. The photographs point to these missing body parts not as voids, but as a kind of matter which, as Aristotle argued, is “bereft of body” (Physics, Book IV Part 1). To examine ‘negatively’ the sculptural fragments through the photographs of their plaster casts, that is, through what is missing in them, is, paraphrasing Gastón Gordillo, to do it by way of those bodies that were negated and that inhabit spectrally the museums of the present.

© Xavier Ribas

Gordillo, Gastón R. Rubble. The Aftermath of Destruction, 2014

Adorno, Theodor Negative Dialectics, 1973

---

Afterlife # 1 to 10

Afterlife #1 [Dying Persian, Palatine Hill, Rome]

Afterlife #2 [Torso, Temple of Aphrodite near Daphni]

Afterlife #3 [Lapith, Temple of Zeus, Olympia]

Afterlife #4 [Theseus and Antilope, Temple of Apollo, Eretria]

Afterlife #5 [Gian, Great Altar, Pergamon]

Afterlife #6 [Lapith and Centaur, Parthenon]

Afterlife #7 [Myrtilus, Temple of Zeus, Olympia]

Afterlife #8 [Grounded Lapith, Parthenon]

Afterlife #9 [Text element (English): Peter Weiss, The Aesthetics of Resistance (Volume 1). Duke University Press, London 2005. Translation: Joachim Neugroschel]

Afterlife #10 [Terme Boxer, Quirinal Hill, near Rome]

---

Afterlife #9 [Spanish version]

Peter Weiss, La estética de la resistencia, Hiru, Hondarrabía 1998.

Traducción: José Luis Sagüés

Afterlife #9 [English version]

Peter Weiss, The Aesthetics of Resistance (Volume 1). Duke University Press, London 2005.

Translation: Joachim Neugroschel

Installation of Afterlife in the exhibition In a Dim Light at the Galeria ProjecteSD, Barcelona, January 2024.

Installation photographs: Roberto Ruiz.